Pointing Upwards, Pointing Downwards

- Brian Young

- Nov 28, 2021

- 8 min read

Message for worship at West Richmond Friends Meeting, 28th of Eleventh Month, 2021 (Advent I)

Speaker: Brian Young

Scripture: Luke 3:1-6, NRSV

In the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler[a] of Galilee, and his brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias ruler of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness. He went into all the region around the Jordan, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins, as it is written in the book of the words of the prophet Isaiah,

“The voice of one crying out in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight.

Every valley shall be filled, and every mountain and hill shall be made low, and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough ways made smooth;

and all flesh shall see the salvation of God.’”

I hope everyone had a blessed Thanksgiving this past week. Stephanie and I did travel; we were in Chicago Wednesday through yesterday, and we spent the holiday with our friends Jason and Michael and a couple of other friends (everyone was vaccinated and had even had their booster shots, so thank God for that ). Jason is an amazing cook, so we brought lots of leftovers home.

As I mention traveling or staying home, I remember that in a time when we have become a blended congregation—Zoom and in-person—“home” no longer defaults to Richmond, Indiana. As the boundaries of active participation for us have expanded to various parts of the U.S. and even abroad, so have the places that we call home. One of the things I am thankful for, in this season, is how well we have weathered this transition to this new way of being a body. We’ve all worked really hard, in various ways, to get to where we are now, even when none of us was sure where that would be, or what that would look like. Some of us have made tremendous sacrifices of time and treasure to make blended worship work. All of us have had to make adjustments to new technology and to new ways of being together. And when some things have not worked entirely well—or when they have not worked at all—we’ve been willing to extend grace to one another. So I give God thanks for all of that, today.

And as we conclude (or perhaps continue in) a season of thankfulness, a new season beckons—a season of seeking and preparation. Kelly and Ava have lit the first candle, and Advent begins.

So we begin with a voice crying, “In the wilderness, prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight,” the Gospel-writer hearkening back to the words of Isaiah the prophet to frame the work of John the Baptist. Actually, Luke doesn’t begin there, quite. First, he has to give us some context, so he tells us who’s in charge: the Emperor Tiberius; local proxy kings Herod Antipas, Herod Philip, and Lysanias; and the high priests Annas and Caiaphas (3:1–2a). Of the four Gospel writers, Luke is probably the one most concerned with connecting the events of Jesus’ life with events in the larger world. One reason for this may be what it says at the very beginning of the Gospel, where Luke writes that he intends to make an “an orderly account” of these events: everything in order, Jesus in his historical context, neat and tidy. (Except that there are some issues with trying to derive a date from the names that Luke mentions; scholars are generally only willing to say this puts us somewhere in the range 25–30 CE).

Another reason for beginning in this way is that it echoes the beginnings of the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible; many of these begin by telling us who was king during the ministry of a particular prophet—for example, Amos 1:1 says that what it records took place “in the days of King Uzziah of Judah and in the days of King Jeroboam... of Israel.” So Luke might have given us this rundown of powerful folks to connect John with the prophetic heritage. Certainly, John shows up here as a prophet—v2 ends, “the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness.” To whom does the word of God come, if not to a prophet?

A friend of mine used to like to say that the work of the prophet is to “announce and denounce”: the prophet announces the great and terrible day of the Lord, and denounces the injustice that the people, or the systems of the world, have been committing. John fulfills both these assignments in Luke 3: in today’s passage, he announces a baptism of repentance; and if you read past verse 6, you’ll see him denouncing the people for their passive complacency, or for their active injustice. So I think we are meant to see John bearing the mantle of the Hebrew prophets who came before him, as he proclaims his baptism of repentance in the wild country around the Jordan.

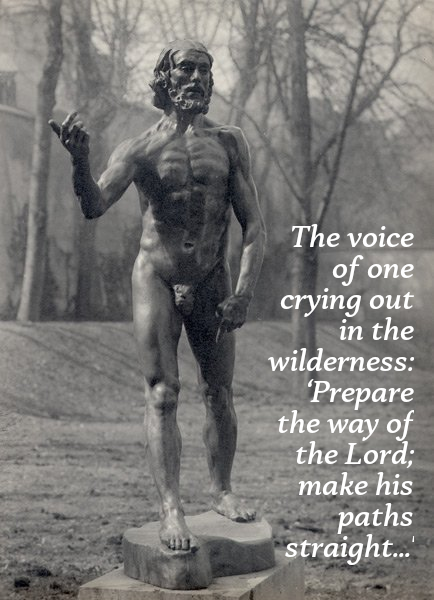

On the front of today’s bulletin is a figure of John the Baptist made by the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin. I was unfamiliar with this depiction of John until sometime last year, when I was introduced to it by Craig Goodworth, the ESR student for whom I was a theological reflection supervisor. As an artist, Craig is drawn to meditation on aesthetics, and so this sculpture of John was the starting point in one of our reflection sessions together. I find this image arresting first of all because, as you have all probably noticed, John is stark naked. Yes, the Gospels of Mark and Matthew tell us that he wore animal hides and rough leather, so shouldn’t he be wearing something? But Luke tells us nothing about his clothing, so perhaps he spent some of his public ministry in the altogether—especially if he was in the water a lot of the time. It could be that Rodin was simply doing another one of his studies of the human form here—many of his other subjects are unclothed (“The Thinker,” for example). But nakedness is in some sense another part of the prophetic vocation. You might remember that the prophet Isaiah was called by God to go naked for three years as a sign against Egypt and other nations (Isaiah 20:1–4). More generally, to be naked before God is to have given up on pretense, to be committed to total honesty and transparency. And to be naked before other people certainly may shock, but it calls them to that same honesty and transparency.

Another thing I notice about Rodin’s sculpted John is that he has been captured in motion. Many depictions of John have him standing, probably with his arms in the air, as he announces and denounces—perhaps pointing towards the people whom he is calling to repentance. But Rodin’s Baptist is striding, active, perhaps preaching as he walks along—maybe he is headed towards the Jordan, and we’re meant to see people following him to be baptized. This reminds me that prophetic work is active work—it’s not sitting on your butt telling people to get right, it’s getting out there to show people how and where they can get right. Certainly, some of the most prophetic voices we’ve heard in recent years have been those of people striding through the streets, denouncing injustice and calling all of us to repentance.

The third thing I notice about this image is John’s hands. I just said that many images of the Baptist have him pointing at someone or some thing, often with an outstretched arm, in what feels like an accusatory gesture.Here, Rodin’s figure is pointing, but not at anybody around him; he uses both hands, one pointing upwards, one pointing downwards. He might be pointing up towards heaven and down towards earth—the charge of the prophet being to bring those two realms together. He might be pointing up towards the one who is to come, and down to himself, the one not worthy even to untie the sandal-thong of the Messiah (Luke 3:16). He might be telling his followers something about baptism—down into the water, and up into new life. There are many other possibilities that I’m sure occur to you. Altogether, I’ve found this particular image of the Baptist to be a new way into the story.

One additional thing to say about those first two verses of the passage, when Luke introduces the powerful men of the day: think about the contrast that they create with this naked man striding into the waters, pointing up towards heaven and down towards earth. Luke identifies the powers, and then identifies one opposed to them—one, in fact, who will be beheaded because of his speaking truth to power.

They are clothed in all manner of fine cloth, in the robes of kings and in the priestly uniform; he is naked before God and humanity.

They sit on their thrones and in their high places of privilege; he is on the move in the wilderness—where perhaps like Jesus he has no place to lay his head—and he bids others to follow him to the river.

The rulers point to themselves, or to the strength of their arms and armies; the priests point to the magnificence of the Temple, or to the Torah, remembering their father Abraham; John points simply to heaven and to earth, as he follows his calling to bring to the two together.

Finally, the rulers and the priests represent the systems of violence and domination, and John points to a new Reign, one that establishes peace by peaceful means, and not by arms. He points also to the One who will inaugurate that Reign, who will bring it in; the One whose sandal he is not fit to untie; the One whose salvation shall be seen by all flesh.

And the One whose arrival, whose coming, we wait for in this season.

Today, with one candle lit, we meditate upon hope. The passage that Luke quotes from the prophet Isaiah at the end of today's passage, “in the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord,” is from a section of Isaiah written to comfort a people in exile—the people of the Israelite kingdoms who had been exiled to Babylon.

And it assures us that God surely comes to the aid and comfort of God's people, even in exile, even in want, even in darkness and desperation, even in a pandemic. This is the central message of Advent: that God has come, and is coming, to our aid.

Living in this hope of God coming to be with God's people is the challenge of Advent. Although our times are very different from those of John the Baptist, we do live in a contemporary Babylon of materialism and corporate power and militarism; and this is a realm in which a pandemic has upended almost all of our expectations, and many of our hopes in earthly things.

Our challenge is to discover anew, and then to proclaim, the liberating message of hope. How is God coming to us, here and now? And how do we explain that to those around us? And are there things, in us, that obstruct God's arrival? Surely we cannot stop the glory of the Lord from being revealed, but we can choose to cooperate with that revelation, or not. We can go with John to the river, or we can turn away. What things within us need to be smoothed out, made plain, lifted up or laid low, in order for the highway of the Lord to be clear in us?

The season of Advent challenges us once again to make the way plain.

Rodin, 1880. Public Domain.

New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/. You are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform this work, as well as to make derivative works based on it, as long as: 1) you attribute whatever part of this work you use to the author, Brian Young, by name; 2) you do not use the work for commercial purposes; 3) you distribute your resulting work only under the same license or a license similar to this one.

Comments